Event-Driven Serverless Architectures

Serverless - the latest and most ‘cloud-native’ approach to developing applications, offers increased agility, improved resilience and scalability, and a pure on-demand consumption-based cost model. However, to truly realize those benefits and deliver more advanced outcomes, we should look beyond the relatively narrow focus on Functions-as-a-Service (FaaS; or related variants such as BaaS (Backend), fPaaS (Function Platform), serverless PaaS, etc.). Basically, it is worthwhile to approach serverless from an architectural perspective; and more specifically, with event-driven serverless architectures.

The focus on FaaS (or function platforms) and the related considerations are still useful, as functions can be applied to a variety of use cases, especially when implemented as point solutions for a gradual decomposition of monolithic architectures into microservices, or as net-new microservices on existing systems to add new functionality (such as in a manner similar to the Sidecar distributed computing pattern). However, other than being able to run singularly focused units of work on an abstraction of immutable infrastructure, what truly differentiates serverless computing, is that it inherently advocates an event-driven architecture design. Thus for this article we want to take a step further, and evaluate the design considerations when using serverless technologies for an entire application architecture. That is, to build a complete cloud-native application using an event-driven serverless architecture.

Architecture Design Principles

Now this isn’t a brand new concept, as serverless computing builds upon microservices and domain-driven design, which builds upon service-oriented architecture (SOA) and event-driven architecture (EDA), which build upon distributed computing best practices, etc. So a lot of the design fundamentals and best practices from the past still apply. Here we discuss a couple that have some unique elements and/or are especially interesting to serverless computing.

- Events over Functions

- Microservices over Monoliths

- Meta over Data

- Distributed over Stateless

- Consumer over Service

- Choreography over Orchestration

- Composition over Integration

More elaboration on these below.

Events over Functions

As we’re alluding to, event-driven serverless architectures are, well, event-oriented. 😉 Even though function platforms support both event-driven and request/response service invocation patterns, we should aim to use an event-driven design as the default service interaction model.

Event-driven design inherently enables loose coupling, which enables service abstraction and isolation, deployment flexibility, independent scale, etc. This is especially relevant to function platforms because functions are inherently fine-grained, and a loosely coupled architecture enables the functions/services to operate independently similar to individual musicians in a jazz ensemble.

That is, loose coupling is key to enabling more smaller components to work effectively together, while leveraging their operational independence, auto-scaling, and on-demand cost models. On the other hand, when services are tightly coupled in a synchronous request/response model, the system behaves more like a monolith (bigger components), and in that case fewer differentiated benefits can be gained from serverless computing.

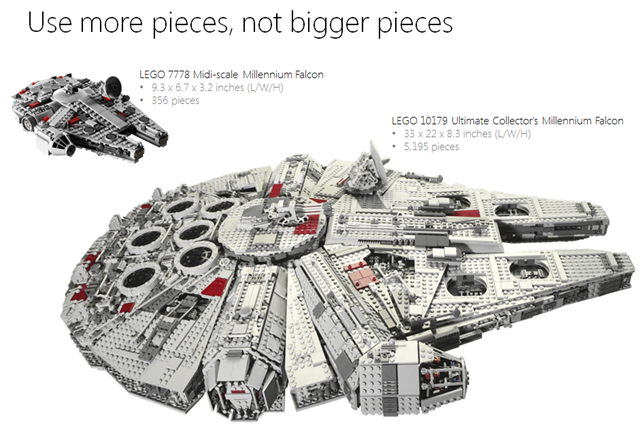

Or, one more analogy with LEGO bricks - we can easily see how the regular LEGO bricks (~4,000 parts) are more flexible and scalable (in terms of the things we can build), than the fewer and larger Duplo bricks. Similarly with serverless computing - we get more agility from a loosely coupled system made up of many fine-grained services.

Thus from a design perspective, taking an events-led approach helps to drive towards an event-driven architecture, which leads into many of the principles below. This means thinking more about events, and organizing application logic as reactive elements to events, where events can represent a change in state (e.g., something happened), or a task submission (e.g., do something). This then leads into functional design, which is the opposite direction than when taking a functions-led approach. The end result is a more loosely coupled architecture that looks like a set of discrete microservices operating independently, working directly with a number of resources (e.g., database, storage, service API’s, etc.), and tied together by events that don’t necessarily map to sequential workflows.

This type of architecture design is especially effective at supporting modern applications with unpredictable scale and user demand. Event-driven design helps with concurrency as it breaks down large sequential transactions into several smaller parallel tasks. Serverless functions help with the operational aspects of auto-scaling and resiliency of individual processes to fulfill these tasks, without the development teams to be concerned with provisioning the necessary infrastructure to manage spikes in demand, and to handle concurrency, while maintaining cost levels accordingly.

Microservices over Monoliths

This isn’t a general statement against monolithic applications, as monoliths are an effective approach for some application scenarios, just as serverless computing isn’t suitable for all application scenarios. However, function platform implementations inherently follow the microservices model, thus a microservices design is favored over a monolithic design.

Of course, we can still deploy monoliths into functions; just let the platform invoke an entry point into the monolithic application. However, a key thought is that smaller programs are less complex than bigger programs (though distributed programming is a different matter). Plus, most function platforms have constraints such as execution duration, memory allocation size, etc. which are likely insufficient for large monoliths. So for serverless computing, systems composed of small, independent, and interconnected units of functionality, are favored over larger bundles of functionality.

Thus, many of the existing best practices in designing microservices apply in serverless computing as well. However, there are some differentiating aspects, such as the concept of decentralized data management, which microservices architectures advocate each ‘service’ to own and encapsulate its database and dependent services, and that other services in a system should not create ‘back doors’ to access those ‘internal’ resources directly.

In event-driven serverless architectures, this could be slightly different as we can further decompose a ‘service’ down to multiple ‘functions’, where a set of functions may need to manage the same set of data (which would be considered an ‘aggregate’). And to maintain a consistent level of serverless-ness, the resources that functions use should align with serverless computing fundamentals as well (e.g., provisionless vs. provisioned resources).

By ‘aggregate’, we mean a set of functions and a set of data that represent a specific domain, and make up a bounded context; consistent with the similar concepts for microservices (or an ‘aggregate’ is kind of like a microservice).

With aggregates, in larger systems we can implement them to help modularize the architecture, so that changes (in function code or data structure) and faults can be isolated and localized in an aggregate without impacting the entire system. And of course, this means that functions external to an aggregate should not have direct access (e.g., ‘back doors’) to the resources mapped to that aggregate; access to an aggregate should go through function interfaces. This architecture would be organized into several aggregates each managing its own resources (like microservices), instead of many functions all working on the same set of data.

For smaller systems and simpler applications, it’s conceivable that a principled approach might add more overhead than benefits. In those cases it might be more effective to prioritize for agility and simplicity instead. Besides, this particular system can be managed as an aggregate later if/when participating in a larger architecture.

Similarly, from a data management perspective, we may need to consider a modular and/or sharded data design approach (e.g., decomposing the database down to smaller collections and keeping certain data collections mapped to a set of functions as an aggregate) instead of enforcing separate physical databases for individual microservices. Serverless databases like Azure Cosmos DB help with this as Cosmos DB provides structures around databases/containers, collections, and partitions, and provides controls on throughput scaling factor, multiple data consistency levels (from eventual to strong), seamless geo-replication with multi-master support, etc. This helps with maintaining separate sets of data without increasing complexities in data management infrastructure.

Thus, even though serverless computing favors a microservices design, we still need to carefully consider the granularity of individual functions (similar to service granularity considerations in SOA, and class/object granularity in OOP, etc.) and how data is managed. One difference for function platforms is that each invocation on a function incurs cost, so trade-offs in cost, performance, service autonomy, change and service versioning management, scale and concurrency, value of agility, etc. need to be considered when deciding whether a unit of work should be decomposed into separate functions, or bundled in one function.

Meta over Data

Event-driven serverless architectures advocate passing metadata instead of actual data, between units of tasks (functions). This is especially relevant as direct cross-function communication is discouraged, and in those scenarios a message queue should instead be used to maintain loose coupling at a system level. However, most message queue solutions also have a limit in message sizes.

From the perspective of events, metadata consists of information that describes ‘something happened’ in the system, specific information relevant to the event, and common logistical elements such as event source, timestamp, and unique identifier.

For example, the storage system publishes an event that a file has been uploaded by a user. The event message itself would only contain the event type (e.g., “file uploaded”), and path/url information to the file. The consumer function of this event can decide what to do with the information, such as to download the file from the storage system and do its work (such as resizing the image into a fixed size and sending it to a computer vision service to recognize its contents) and then write data resulting from the work into the database, related to the user’s account. The user’s account lookup required this function to extract the internalized identifier from the path/url (container assigned to the user) and query the database to access the account information.

Hence the related thought earlier regarding distributed data management in microservices design. Since direct, synchronous request/response between functions is not encouraged, sometimes we can get away with not creating atomic data ‘read’ functions to be invoked by functions that need to lookup data; but writes should be submitted to a function to ‘do the work’. This means building on an eventual consistency model provided by a serverless database solution (such as Azure Cosmos DB), and use the platform bindings to execute read queries directly from the database. Though of course, thoughts around aggregates and implementing decentralized data management solutions still apply, as in larger systems it does make sense to enforce data access through a function when trade-offs weigh in this direction.

Metadata from this perspective should be immutable and not dependent on application state. Instead, user and application state should be maintained in a database solution that ensures data integrity and consistency, so no state is maintained in the form of events that live outside of the serverless database.

Distributed over Stateless

While functions should be written to be stateless (shared nothing) and idempotent (consistently same output from same input), the composite system (end-to-end architecture) in most cases does maintain application state in some form. The distinction is that, processes (functions) should be stateless, similar to events (that carry only metadata), so that any state is only maintained by stateful resources.

These resources can be serverless databases, distributed storage, message queue solutions, and other service API’s (that are implemented by their own architectures with data and dependencies encapsulated). From this perspective, application state is distributed among a set of resources in a system, and not stored and managed in a centralized resource. These platform resources themselves should operate in a model that aligns with event-driven serverless architectures (or microservices), with a consistent level of independent resiliency and scalability.

For example, Azure Cosmos DB may be the primary serverless database resource in Azure, but instead of thinking of it as one centralized database, application state should be decomposed into separate databases or collections mapped to relevant sets of functions, or use partitions and sharding for larger data sets. Basically, follow the microservices best practices in domain-driven design, where a function/data aggregate works with its own domain model within a bounded context (and use of canonical models is discouraged to minimize contention). Then there could also be files in Blob Storage, vertically aligned data in Table Storage, transient data in Redis Cache, etc. And when possible, push user session state to the client, such as in the cases of mobile apps, rich HTML/JS client apps (e.g., Single Page Apps).

As a result, application state is distributed across the platform resources used in an architecture. From a design perspective, following a distributed state approach (system-oriented as opposed to focus on ‘stateless’) and leverage the resources to do their work, enables functions to be stateless (as a result), and reach a consistent level of serverless-ness in the composite system architecture.

Consumer over Service

An event-driven model enables us to take a more consumer-centric approach to designing API’s for services (as opposed to service-centric). And specifically for event-driven serverless architectures, it is more effective to approach the designs of events and interactions between functions and resources from a consumer (or user, client, publisher) perspective.

Traditionally, the design of a system tends to be driven from the back-end; by first defining the data models, then application processes to manage the data, then service interface definitions to expose functionality to consumers. The consumer of these services then is responsible for understanding the service domain, the semantics of the service API’s, and often needs to grapple with a client SDK (which is needed to simplify interactions with service API’s), etc. As a result, the application design is service-centric, in that the onus is on the consumer to conform to the requirements of the services.

Taking a functions-led approach also tends to drive the design from the backend (service-centric). However, because of the loose coupling enabled in an event-driven model, we can drive the design from the frontend; using a consumer-centric (or user, client, publisher) perspective. This is because in an event-driven model, the event publisher (traditionally client/consumer role) drives the definition of the event, then it simply submits the event into an eventing system (or queue infrastructure), without any knowledge of the implementation details of the subscriber (traditionally service role). The onus is then on the subscriber (service) to adapt to the event and do its work.

Of course, technically we can still have the service implementation to define how an event message needs to look like (e.g., an exact JSON document format) that event publishers need to adhere to. But if we take a consumer-oriented approach, and leverage the function platform’s built-in capabilities such as agile code deployments, versioning, proxies, API mediation, etc. (to help with propagating design changes from front to back), we would end up having a more flexible system that is more agile and adaptable to business and technical changes.

Choreography over Orchestration

The design of workflows or logical processes in an event-driven architecture should land in a choreography model, as opposed to an orchestration model.

An orchestration model points to a centralized process-driven view of sequential workflow, mostly aligned with synchronous request/response process that tightly manages the end-to-end execution of logic and interaction directly with resources and services to complete a transaction. A choreography model points to independent services that observe the system and react to events autonomously, to accomplish a logical task collectively. The subtle difference is that orchestration is a centralized process-centric view, vs. choreography is a distributed resources and functions-oriented view.

Basically, this highlights the thought to resist the urge to design workflows as traditional sequential (or in a way, monolithic) processes in a service implementation. Rather, approach the design from the use of resources needed for a task, then logic in functions to interact with the resources, and invoked via events. Consequently, a logical transaction in an event-driven architecture may result in the execution of multiple parallel tasks activated by events that represent changes in resources. These tasks have no knowledge of each other’s execution and implementation details, but the collective result of their work accomplishes the intended output of a logical user/system transaction.

Composition over Integration

The design of interactions between resources and functions should use more of a service composition approach, than service integration.

Service integration approaches tend to land in synchronous interactions that are tightly coupled, and sometimes need to embed client SDK’s to abstract the service API implementation, which also ends up tightly coupling the service implementation. This cannot be avoided when interacting with resources directly, but we can leverage the function platforms built-in capabilities to abstract service implementations as input and output bindings. Bindings provide a declarative way to connect to resources in a system, so that function implementations can avoid including details of the resources and their service API’s.

Integration solutions still play a significant role in the system. What this principle advocates is to be mindful of when/where which of these patterns/models are applied in the architecture design.

Abstracting resource communication details into declarative bindings is a mechanism to accomplish a form of loose coupling. It enables agile changes in how resources are used and accessed, and moves development focus towards designing workflows that compose of various resources and services. A compositive system provides higher agility to respond to business and technical changes, and enables an end-to-end system to be managed as a tangible product (not just the user-facing assets), responding to customer demand quickly and effectively. This is the key benefit for adopting cloud-native serverless platforms, especially when balanced against relevant design trade-offs.

A Simple Example

Here we walk through an over-simplified view of how an event-driven serverless architecture differs from a monolithic architecture.

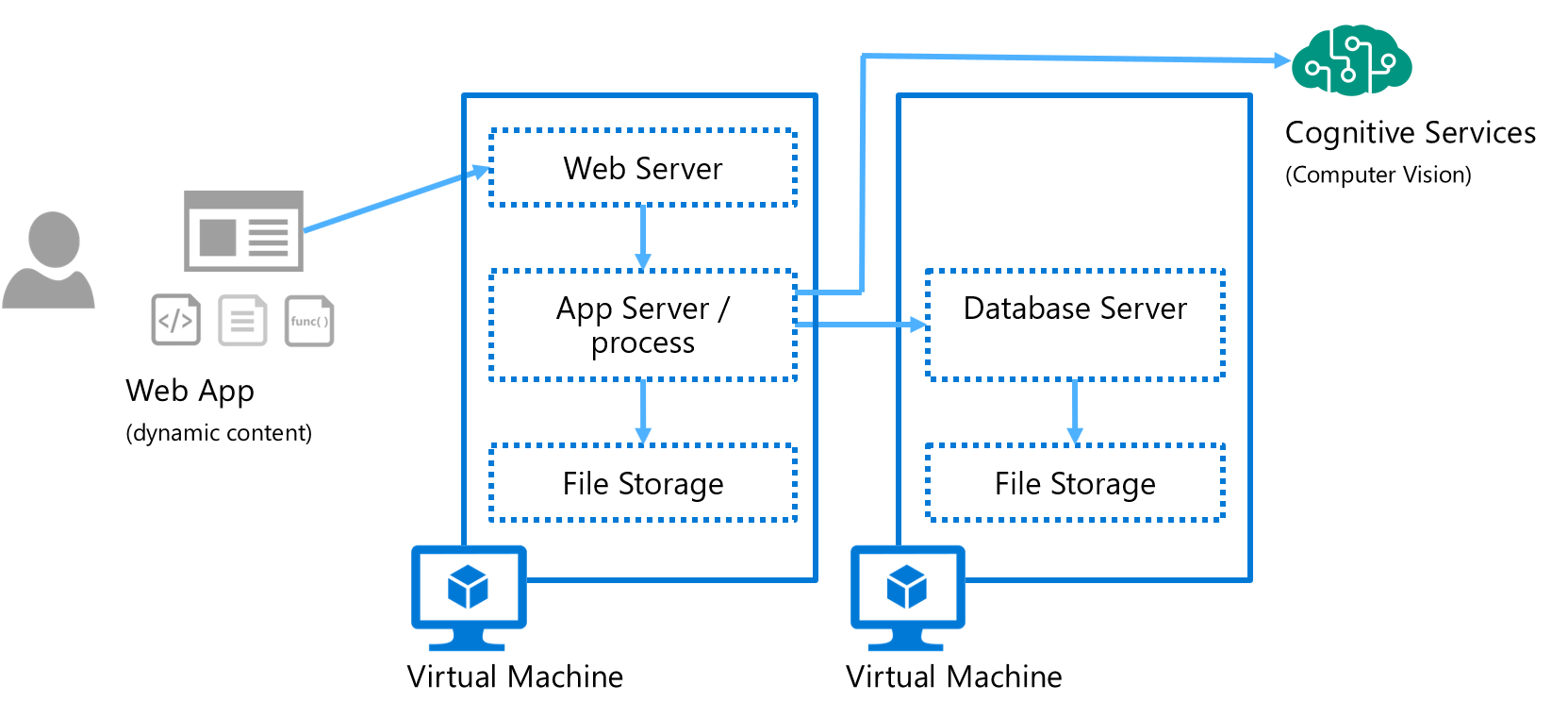

We start with a typical web app view of a monolithic application, with these characteristics:

- Monolithic application: all functions of this application are bundled together and hosted in an App Server process, with hard dependencies on other resources such as a Web Server frontend, file storage (local or mounted distributed disks), and a centralized database in another server tier. Modular design or forms of loose coupling can be achieved, but mostly encapsulated within the confines of the monolithic application process, and changes are typically released as updates to the entire implementation

- Orchestration model: the server process is invoked in a synchronous request/response model, and directly controls/manages the flow of application logic and use of resources and external services (Cognitive Services in this view) to accomplish the unit of work

- Centralized state: data and state are managed by centralized resources and shared between application processes. Reuse is a key benefit

- Integration model: code, components, processes, and resources are tightly coupled end-to-end in a synchronous and sequential processing model

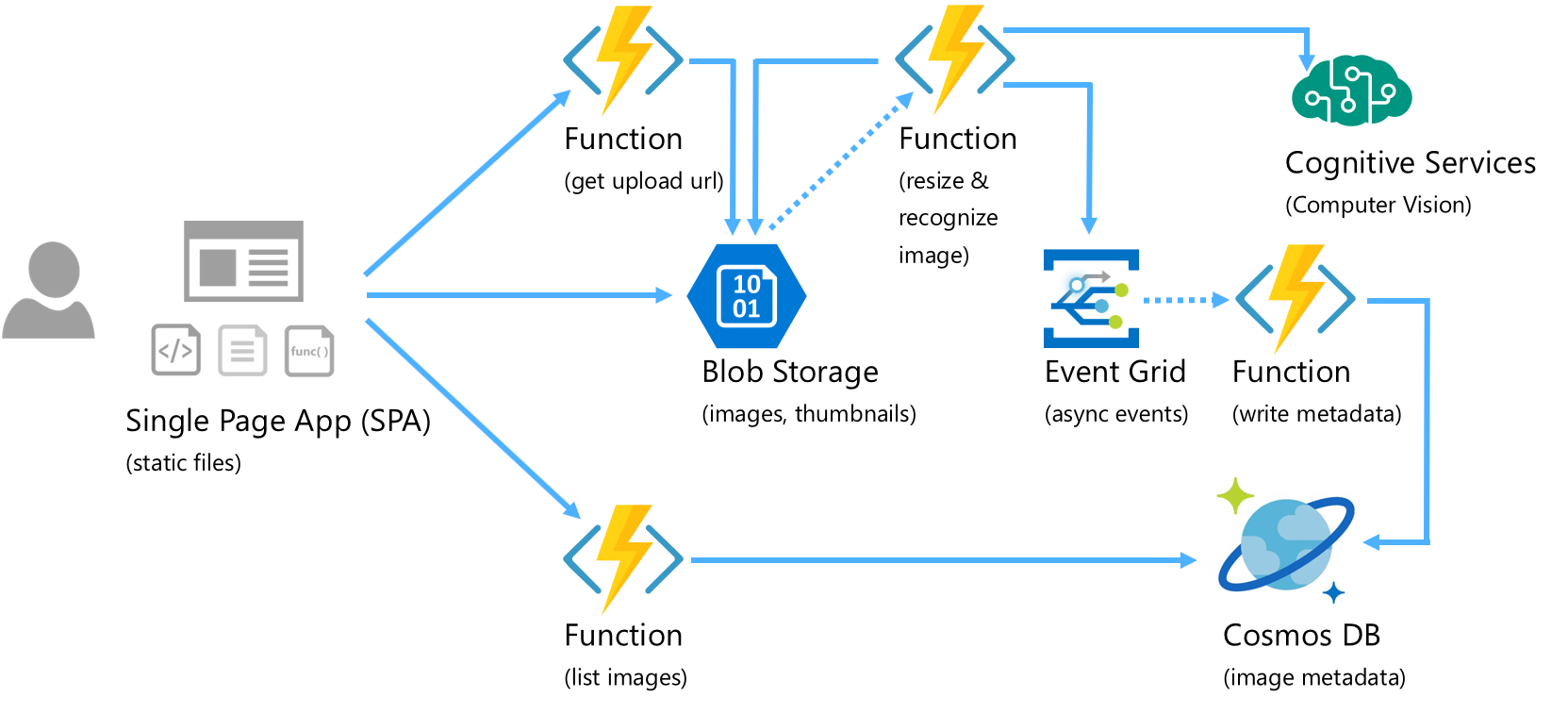

This application, when implemented using an event-driven serverless architecture, could look like this (saving the technical details of this implementation for another time).

Similarly, this serverless implementation has these characteristics:

- Microservices application: the application process is decomposed into independent functions reacting to events autonomously, that operate on immutable infrastructure which plays the role of traditional server environments (but abstracted into a cloud environment; not individual servers). Each function can be updated and scaled independently, and failures are isolated. As in typical serverless environments, this architecture does not use any provisioned compute resources. That is, no idle servers listening on ports waiting for user requests. The entire architecture scales seamlessly from 0 to any load, and can expand deployment to more cloud regions when needed.

- Choreography model: work in this system is accomplished in a non-linear model; services get activated as conditions/changes (or events) arise. There is no longer a traditional sequential workflow view, but the collective results of the autonomous services and resources accomplish the unit of work

- Distributed state: data and state are managed by distributed resources (e.g., client state in the single page app (SPA), files in Blob Storage, modularized and domain-specific data in Cosmos DB, etc.). No compute resources are allocated for state and data maintenance resources (e.g., no need for an FTP process/server, file server, provisioned database server, etc.; these are now all resources aligned to the serverless model with similar on-demand consumption-based cost models)

- Composition model: functions and resources interact with each other with communication and connection details abstracted, enabling quick composition of new services and resources to bring value to market faster, and experimentation scenarios

A Few More Thoughts

An event-driven serverless architecture is not without its trade-offs. It isn’t suitable for all application scenarios such as ones with long-running jobs, processes with high memory requirements, workloads that require predictable performance, etc. It also requires re-architecting applications into minimal-latency microservices, and decompose data sets into smaller domains and maintained in bounded contexts mapped to function/data aggregates. And, a highly distributed architecture inherently distributes points of control and escalates system complexity, which correspondingly increases challenges in the operations and management of an end-to-end architecture.

There are some similarities to the discussion and comparison between monolithic kernels and microkernels in the operating systems design domain. Monolithic kernels, even though larger and more prone to errors (something crashes and can impact the entire process), have better performance (because everything is kept in the same address space) and are simpler to maintain (require less code). Microkernels run user and kernel services in different processes (different address space; distributed processes), so they are less prone to errors (better isolation and more secure) and updates are componentized (localized), but execute slower and more complex to maintain (require more code). Design trade-offs, essentially; and similar comparisons can be drawn between monolithic application and microservices application architectures.

Specifically with event-driven serverless architectures, there are additional areas that are worth exploring, such as those below; but we will save them for another time:

- Security

- Performance

- Operations (the Ops in DevOps; as function platforms make the Dev part simpler, but not the Ops part)

- Change management and versioning, and experimentation

- error handling

- transaction monitoring and tracing

- A/B, blue-green, canary testing

- Organizational culture and team dynamics

- Economics and business case

Thus, serverless computing isn’t a replacement to other models in modern computing; it is another option in the toolbelt, that when implemented effectively against suitable scenarios, can help improve resiliency and scalability, and agility and faster time to market. These key benefits of serverless computing are especially relevant to the modern class of application scenarios.