Using Events in Highly Distributed Architectures

Summary: SOA succeeded in getting loose coupling at a technical level; now, let us go for the same at a business-process level.

Introduction

Many service-oriented architecture (SOA) efforts today are focusing on implementing synchronous request-response interaction patterns (sometimes using asynchronous message delivery) to connect remote processes in distributed systems. While this approach works for highly centralized environments, and can create loose coupling for distributed software components at a technical level, it tends to create tight coupling and added dependencies for business processes at a functional level. Furthermore, in the migration towards real-time enterprises, which are also constantly connected and always available on the Web, organizations are encountering more diverse business scenarios and discovering needs for alternative design patterns in addition to synchronous request-driven SOA.

Event-driven architecture (EDA, or event-driven SOA) is often described as the next iteration of SOA. It is based on an asynchronous message-driven communication model to propagate information throughout an enterprise. It supports a more “natural” alignment with an organization’s operational model by describing business activities as series of events, and does not bind functionally disparate systems and teams into the same centralized management model. Consequently, event-driven architecture can be a more suitable form of SOA for organizations that have a more distributed environment and where a higher degree of local autonomy is needed to achieve organizational agility. This article discusses how EDA, together with SOA, can be leveraged to achieve a real-time connected system in highly distributed environments, and be more effective at understanding organizational state. We will then discuss a pragmatic approach in designing and implementing EDA, while considering the trade-offs involved in many aspects of the architecture design.

Event-Driven Architecture

So, what do we mean by events? Well, events are nothing new. We have seen various forms of events used in different areas such as event-driven programming in modern graphical user interface (GUI) frameworks, SNMP and system notifications in infrastructure and operations, User Datagram Protocol (UDP) in networking, message-oriented middleware (MOM), pub/sub message queues, incremental database synchronization mechanisms, RFID readings, e-mail messages, Short Message Service (SMS) and instant messaging, and so on.

In the context of SOA however, an event is essentially a significant or meaningful change in state. And an event in this perspective takes a higher level semantic form where it is more coarse-grained, and abstracted into business concepts and activities. For example, a new customer registration has occurred on the external Website, an order has completed the checkout process, a loan application was approved in underwriting, a market trade transaction was completed, a fulfillment request was submitted to a supplier, and so on. Fine-grained technical events, such as infrastructure faults, application exceptions, system capacity changes, and change deployments are still important but are considered more localized in terms of scope, and not as relevant from an enterprise-level business alignment perspective.

As event sources publish these notifications, event receivers can choose to listen to or filter out specific events, and make proactive decisions in near real-time about how to react to the notifications. For example, update customer records in internal systems as a result of a new customer registration on the Website, update the billing and order fulfillment systems as a result of an order checkout, update customer account as a result of a back office process completion, transforming and generating additional downstream events, and so on.

Event-driven architecture is an architectural style that builds on the fundamental aspects of event notifications to facilitate immediate information dissemination and reactive business process execution.

In an event-driven architecture, information can be propagated in near-real-time throughout a highly distributed environment, and enable the organization to proactively respond to business activities. Event-driven architecture promotes a low latency and highly reactive enterprise, improving on traditional data integration techniques such as batch-oriented data replication and posterior business intelligence reporting. Modeling business processes into discrete state transitions (compared to sequential process workflows) offers higher flexibility in responding to changing conditions, and an appropriate approach to manage the asynchronous parts of an enterprise.

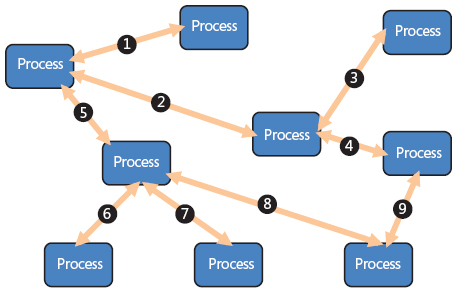

Figure 1. Request-driven architecture (logical view)

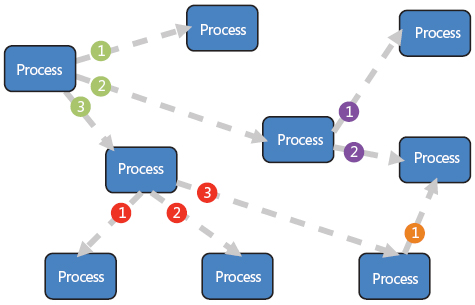

Figure 2. Event-driven architecture (logical view)

Fundamental Principles

The way systems and business processes are connected in an event-driven architecture represents another paradigm shift from request-driven SOA. Here, we will discuss some of the fundamental aspects.

Asynchronous “Push”-Based Messaging Pattern

Instead of the traditional “pull”-based synchronous request/response or client/server RPC-style interaction models, event-driven architecture builds on the pub/sub model to “push” notifications out to interested listeners, in a “fire-and-forget” (does not block and wait for a synchronous response), uni-directional, asynchronous pattern.

Autonomous Messages

Events are transmitted and communicated in the form of autonomous messages — each message contains just enough information to represent a unit of work, and to provide decision support for notification receivers. Each event message also should not require any additional context, or any dependencies on the in-memory session state of the applications; it is intended to communicate the business state transitions of each application, domain, or workgroup in an enterprise.

For example, an externally-facing Web application publishes an event that a new customer registration was completed with these additional attributes: timestamp, ID=123, type=business, location=California, email=jane@contoso.com; information that is relevant to the rest of the enterprise, and supports any process-driven synchronous lookups for additional details to published data services from distributed systems.

Higher decoupling of distributed systems

This asynchronous message-based interaction model further encapsulates internal details of distributed systems in an environment. This form of communication does not need to be as concerned with some aspects of request-response models such as input parameters, service interface definitions such as WSDL in SOAP-based communication and hierarchical URI definitions in REST-based communication, and fine-grained security. The only requirement is a well-defined message semantic format, which can be implemented as plain old XML-based (POX) payload.

The event-driven pattern also logically decouples connected systems, compared to the technical loose-coupling achieved in the request-driven pattern. That is, functional processes in the sender system, where the business event took place, do not depend on the availability and completion of remote processes in downstream distributed systems. Whereas in a request-driven architecture, the sender system needs to know exactly which distributed services to invoke, exactly what the provider systems need in order to execute those services, and depends on the availability and completion of those remote functions in order to successfully complete its own processing.

Furthermore, the reduced logical dependencies on distributed components also have similar implications on the physical side. In synchronous request-driven architectures, connected and dependent systems are often required to meet the service-level requirements (i.e., availability and throughput) and scalability/elasticity of the system that has the highest transaction volume. But in asynchronous event-driven architectures, the transaction load of one system does not need to influence or depend on the service levels of downstream systems, and allows application teams to be more autonomous in designing their respective physical architectures and capacity planning.

This also means that changes to each connected system can be deployed more independently (and thus more frequently) with minimal impact to other systems, due to the overall reduced dependencies.

In the case of an externally facing Web application that has just completed a new customer registration process, that information needs to be communicated to an internal customer management system. The Web application’s only concern is to publish the event notification according to previously defined format and semantics; it does not need to remotely execute a service in the customer management system to complete its own processing, or bind the customer management system into a distributed transaction to make sure that the associated customer data is properly updated. The Web application leaves the downstream customer management system to react to the event notification and perform whatever it needs to do with that information.

Receiver-Driven Flow Control

The event-driven pattern shifts much of the responsibility of controlling flow away from the event source (or sender system), and distributes/delegates it to event receivers. Event source systems do not need to explicitly define the scope of distributed transactions and manage them, or connected systems are less dependent on centralized infrastructure components such as transaction process systems (TPS), business process management (BPM), and enterprise service bus (ESB) products. The connected systems participating in an event-driven architecture have more autonomy in deciding whether to further propagate the events, or not. The knowledge used to support these decisions is distributed into discrete steps or stages throughout the architecture, and encapsulated where the ownerships reside, instead of burdening the transaction-initiating sender systems with that knowledge.

For example, in the new customer registration event scenario, the customer management system that receives the event notification owns the decision on executing a series of its own workflows, populating its own database of this information, and publishing a potentially different event that the marketing department may be interested in. All these downstream activities rely on decisions owned and made at each node, in a more independent and collective model.

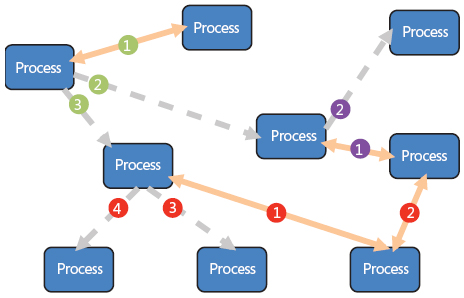

Figure 3. Hybrid request and event-driven architecture (logical view)

Near Real-Time Propagation

Event-driven architecture is only relevant when events are published, consumed, and propagated in near real-time. If this approach is applied in passive event-processing scenarios such as batch-oriented fixed schedule, then its effectiveness is not much different from the traditional data integration techniques used today.

This is primarily due to a simple fact: Events that are “in-motion” are much more valuable than events that are “at rest.” Gaining accurate and near real-time insight has been a complex and difficult challenge for enterprises; even with the advent of SOA, it is still relatively complicated given the existing focus on integrating distributed processes in synchronous interaction models. Event-driven architecture provides a comparatively simpler approach to achieve near–real-time information consistency, as we just need to apply a different form of system interaction model using existing technologies and infrastructure investments.

Potential Benefits

By now, some potential benefits of using an event-driven architecture pattern may have become more apparent:

Effective data integration — In synchronous request-driven architectures, focus is typically placed on reusing remote functions and implementing process-oriented integration. Consequently, data integration is not well supported in a process-oriented model, and is often an overlooked aspect in many SOA implementations. Event-driven architecture is inherently based on data integration, where the events disseminate incremental changes in business state throughout the enterprise; thus it presents an effective alternative of achieving data consistency, as opposed to trying to facilitate data integration in the process layer.

Reduced information latency — As distributed systems participate in an event-driven architecture, event occurrences are enabled to ripple throughout the connected enterprise in near real-time. This is analogous to an enterprise nervous system where the immediate propagation of signals and notifications form the basis of near real-time business insight and analytics.

Enablement of accurate response — As business-critical data propagates throughout the enterprise in a timely manner, operational systems can have the most accurate, current view of the state of business. This enables workgroups and distributed systems to provide prompt and accurate business-level responses to changing conditions. This also moves us closer to being able to perform predictive analysis in an ad hoc manner.

Improved scalability — Asynchronous systems tend to be more scalable than synchronous systems. Individual processes block less and have reduced dependencies on remote/distributed processes. Also, intermediaries can be more stateless, reducing overall complexity. Similar points can be made for reliability, manageability, and so forth.

Improved flexibility — Discrete event-driven processes tend to be more flexible in terms of the ability to react to conditions not explicitly defined in statically structured sequential business processes, as state changes can be driven in an ad hoc manner. And as mentioned earlier, the higher level of decoupling between connected systems means changes can be deployed more independently and thus more frequently.

Improved business agility — Finally, the ultimate goal of SOA implementations. Event-driven architecture promises enhanced business agility, as it provides a closer alignment with operational models, especially in complex enterprise environments consisting of diverse functional domains and requiring high degrees of local autonomy. Also, business concepts and activities are modeled in simpler terms with responsibilities appropriately delegated to corresponding owners. This creates an environment where decisions and business processes in one area are less dependent on the overall enterprise environment, compared to synchronous request-driven architecture’s centralized view of logically coupled, sequentially structured business processes, where one component is often dependent on a number of distributed components for its processing. The reduced dependencies allow technical and functional changes to be planned and released more independently and frequently, achieving a higher level of IT agility and, hence, business agility.

Aspects of Implementation

At a high level, event-driven architecture models business operations and processes using a discrete state machine pattern, whereas request-driven architecture tend to use more structurally static sequential flows. This results in some fundamental differences between the two architectural styles, and how to design their implementation approaches. However, the two architectural styles are not intended to be mutually exclusive; they are very complementary to each other as they address different aspects of operational models in an organization. Furthermore, it is the combination of request-driven and event-driven architectures that makes the advanced enterprise capabilities achievable. Here, we will discuss some of the major consideration areas, from the perspective of building on top of existing service-oriented architecture principles.

Event Normalization and Taxonomy

First and foremost, event-driven architecture needs a consistent view of events, with clearly defined and standardized taxonomy so that the events are meaningful and can be easily understood—just as when creating enterprise-level standards of data and business process models, an enterprise-level view of events needs to be defined and maintained.

Process Design and Modeling

Modeling business processes into discrete event flows is similar to defining human collaboration workflows using state machines. A key is to distinguish between appropriate uses of synchronized request-driven processes or asynchronous event-driven processes.

For example, one organization used the synchronous request-driven pattern to implement a Web-based user registration process, in terms of populating data between multiple systems as a result of the registration request. The implementation leveraged an enterprise service bus solution, and included three systems in a synchronized distributed transaction. The resulting registration process waited until it received “commit successful” responses from the two downstream systems, and often faulted due to remote exceptions. It was a nonscalable and error-prone solution that often negatively affected end users for a seemingly simple account-registration process. On the other hand, as discussed previously, this type of scenario would obtain much better scalability and reliability if an asynchronous event-driven pattern was implemented.

However, if in this case the user registration process requires an identity proofing functionality implemented in a different system, in order to verify the user and approve the registration request, then a synchronous request-response model should be used.

As a rule of thumb, the synchronous request-driven pattern is appropriate when the event source (or client) depends on the receiver (or server) to perform and complete a function as a component of its own process execution; typically focused on reusing business logic. On the other hand, the asynchronous event-driven pattern is appropriate when connected systems are largely autonomous, not having any physical or logical dependencies; typically focused on data integration.

Communication

Event-driven architecture can leverage the same communication infrastructure used for service-oriented architecture implementations. And just the same as in basic SOA implementations, direct and point-to-point Web services communication (both SOAP and REST-based) can also be used to facilitate event-driven communication. And standards such as WS-Eventing and WS-Notification, even Real Simple Syndication (RSS) or Atom feeds can be used to support delivery of event notifications.

However, intermediaries play a key role in implementing an event-driven architecture, as they can provide the proper encapsulation, abstraction, and decoupling of event sources and receivers, and the much-needed reliable delivery, dynamic and durable subscriptions, centralized management, pub/sub messaging infrastructure, and so on. Without intermediaries to manage the flow of events, the communication graphs in a point-to-point eventing model could become magnitudes more difficult to maintain than a point-to-point service-oriented architecture.

Event Harvesting

The use of intermediaries, such as the modern class of enterprise service bus solutions, message-oriented middleware infrastructure, and intelligent network appliances, further enhance the capability to capture in-flight events and provide business-level visibility and insight. This is the basis of the current class of business activity monitoring (BAM) and business event management (BEM) solutions.

Security

Security in event-driven architecture can build on the same technologies and infrastructures used in service-oriented architecture implementations. However, because of the highly decoupled nature of event-driven patterns, event-based security can be simpler as connected systems can leverage a point-to-point, trust-based security model and context, compared to the end-to-end security contexts used in multistep request-driven distributed transactions.

Scope of Data

So, how much data should be communicated via events? How is this different from traditional data replication? Data integration is intrinsic to event-driven architecture, but the intention is to inform other system “occurrences” of significant changes, instead of sending important data as events over the network. This means that only the meaningful data that uniquely identifies an occurrence of a change should be part of the event notification payload, or in other words, just an adequate amount of data to help event receivers decide how to react to the event. In the example discussed earlier with the customer registration event, the event message does not need to contain all user data elements captured/used in the customer registration process, but the key referential or identifying elements should be included. This helps to maintain clear and concise meaning in events, appropriate data ownerships, and overall architectural scalability. If downstream systems require more data elements or functional interaction to complete their processes, alternative means, such as synchronous Web services communication, can be used to facilitate that part of the communication.

State of the Art

Here, we will discuss several emerging trends that influence advanced applications of event-driven processing.

Complex Event Processing

So far, we have only explored using individual events as a means of information dissemination and achieving enterprise-wide business state consistency across highly distributed architectures. Multiple events can be interpreted, correlated, and aggregated based on temporal, historical, and/or computational algorithms to discern meaningful patterns. Basically, in addition to the information individual events carry, combinations (or the lack) of multiple events can provide significant meaning.

Similar capabilities can be found in today’s SOA implementations, but are typically implemented locally to a system examining a request against historical and environmental data at rest, where visibility is limited and interpretation rules are encapsulated. But the use of service intermediaries provides centralized event management, higher visibility, and more relevant interpretation of event streams. Also, as complex event processing often makes use of rules engines to drive the pattern recognition behaviors, changes to how events are processed can be deployed quickly, allowing business decisions to be implemented quickly.

This information can also be derived into composite or synthetic events to prompt downstream actions. For example, in practice today, complex event processing is often used in fraud detection to identify pattern consistency (for example, banking transactions conducted in the same geography), pattern anomaly (for example, a transaction requested from a different geography when other requests are consistently within the same geography), and even lack of events. As soon as the fraud-detection rule identifies a potential attack, the monitoring system can send that information as another event to alert other systems in the enterprise, where specific actions can be taken in response to this event.

Events in the Cloud

As we move towards cloud computing, event processing can also be leveraged to capture and correlate event streams running in the open cloud. However, unlike event-driven architectures within an enterprise, where the focus is organizing business state changes in distributed systems into a consistent view, integrating event streams from the public cloud follows a much less structured form and approach, as the data and context in publicly available events are highly heterogeneous. Information latencies are also expected to be higher in the open cloud. From an implementation perspective, tapping into public event streams could be as simple as subscribing to RSS or Atom feeds directly from other Websites and organizations (including feed aggregators), direct point-to-point Web services integration (either via SOAP-based SOA or REST-based WOA approaches), or facilitated through the emerging class of cloud-based “Internet service bus” intermediaries (such as Microsoft’s Cloud Services platform) where message delivery, service levels, identity and access control, transactional visibility, and contextualized taxonomies can be more formally managed between multiple enterprises. Consequently, the interpreted information from cloud-based event streams can be correlated against event streams internal to an enterprise. The result is a highly reactive enterprise that is cognitive of market and environmental changes as they occur, in which business decisions (whether manual or automated) can be made with significantly higher relevancy.

Context-Aware Computing

The next perceived step in business application architecture is towards context-aware computing. Context from this perspective refers to information that is not explicitly bound to the data elements of a particular process or transaction, but is relevant via implicit relationships. For example, geo-location, time (of the day, week, month, seasons, holidays, special occasions), real-life events such as presidential elections, Olympic games (for example, subsequent potential impact on retailers and their supply chains), stock market conditions, interest rates, raw material over supply or shortage, new media blockbuster hit, new invention, and even weather, can all be information (or event occurrences) that influence human behaviors and decisions, which also convert into interactions with online systems. This contextual information is useful as it provides additional decision support factors, but most importantly, aids towards understanding user intent, such that different responses can be generated for similar requests, influenced by different contextual factors. As a result, context-aware systems are much more connected with the environment and thus can be more relevant, compared to today’s systems that are mostly siloed within the limited views of their own databases.

Event-driven architecture can play a key role in facilitating context-aware computing, as it is the most effective and scalable form of data integration for highly distributed architectures. As discussed previously in this article, higher level decoupling of distributed systems and reduced dependencies in event-driven architectures can significantly simplify efforts in harvesting and interpreting business events within an enterprise, plus tapping into massive amounts of cloud-based events. As a result, event-driven architecture can help systems keeping an accurate pulse of its relevant environments, and becoming more context-aware.

Conclusion

Event-driven architecture brings about the convergence of disparate forms of internal and external events, such as system and IT management notifications, business activities and transactions, public market, technical, and social events. The organization of these events into a unified and consistent view promises enhanced alignment between business and IT, and moves towards a connected, dynamic enterprise that has accurate and consistent business insight, and can proactively respond to changing conditions in near real-time.

However, asynchronous event-driven architecture is not intended to be a replacement of existing forms of synchronous request-driven service-oriented architectures. In fact, they are very complementary to each other when appropriately modeling the different aspects of an organization’s operational model. From a technical perspective, event-driven architecture can be implemented on top of an existing service-oriented infrastructure, without adding more dependencies and complexities. An effective mix of both architectural patterns will create a highly consistent and responsive enterprise, and establish a solid foundation for moving towards always-on and always-connected environments.

Resources

- “Complex Event Processing in Distributed Systems,” David C. Luckham and Brian Frasca, Stanford University Technical Report CSL-TR-98-754. (http://pavg.stanford.edu/cep/fabline.ps)

- “Event-Based Execution Architectures for Dynamic Software Systems,” James Vera, Louis Perrochon, David C. Luckham, Proceedings of the First Working IFIP Conf. on Software Architecture. (http://pavg.stanford.edu/cep/99wicsa1.ps.gz)

- “Complex Event Processing: An Essential Technology for Instant Insight into the Operation of Enterprise Information Systems,” David C. Luckham, lecture at the Stanford University Computer Systems Laboratory EE380 Colloquium series. (http://pavg.stanford.edu/cep/ee380abstract.html)

- “Service-Oriented Architecture: Developing the Enterprise Roadmap,” Anne Thomas Manes, Burton Group. (http://www.burtongroup.com/Client/Research/Document.aspx?cid=136)

- “The Unification of SOA and EDA and More,” Randy Heffner, Forrester. (http://www.forrester.com/Research/Document/Excerpt/0,7211,35720,00.html)

- “Clarifying the Terms ‘Event-Driven’ and ‘Service-Oriented’ Architecture,” Roy W. Shulte, Gartner. (http://www.gartner.com/DisplayDocument?doc_cd=126127&ref=g_fromdoc)

- “Event-Driven Architecture Overview,” Brenda M. Michelson, Patricia Seybold Group. (http://www.psgroup.com/detail.aspx?id=681)

David Chou is an architect in the Developer & Platform Evangelism group at Microsoft, where he collaborates with local organizations in architecture, design, and proof-of-concept projects. David enjoys helping customers create value by using objective and pragmatic approaches to define IT strategies and solution architectures. David maintains a blog at http://blogs.msdn.com/dachou, and can be reached at david.chou@microsoft.com.

This article was published in the Architecture Journal, a print and online publication produced by Microsoft. For more articles from this publication, please visit the Architecture Journal Web site.

(originally published at https://msdn.microsoft.com/en-us/library/dd129913.aspx)