Multiple Inheritance

It was back in 2008 when I first wrote about .NET and Multiple Inheritance. Since then I have received many feedback (some were particularly pointed), though kind of amazed that this is still a subject of debate even today.

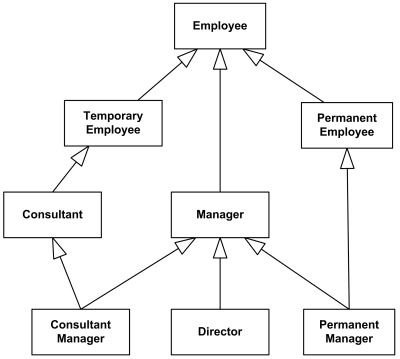

(from https://www.uml-diagrams.org/generalization.html)

To clarify - I don’t think multiple inheritance is inherently ‘bad’; I think it is an elegant solution for when we do want to inherit implementation and/or state from parent/super classes (such as classes that have orthogonal behaviors). But I am fascinated by the diverse perspectives on this language construct, and how different approaches were taken in designing Java and C#, which don’t support multiple inheritance of implementation and state (some think that inheritance of type, or interfaces, is a form of inheritance too but I tend to think of that as design by contract using abstract types as opposed to inheritance).

Design Principles

From a design perspective, I am also intrigued by decisions to not add/include features, just as I do with features that are included. With multiple inheritance, I think it boils down to a ‘simple’ thought - the designers for Java and C# made the decision to not include it, for sake of simplicity.

It was a design decision.

And like typical design decisions, it was a judgment call based on the assessment made by the design team, by weighing trade-offs between the merits and costs of a particular product feature. Especially important is how a particular feature is considered within the context of the overall system it participates in.

From a systems perspective, Java and C# were intended to support newer classes of applications and environments, thus different approaches were taken, and many represented departures from C++ (or - why invent a new language that essentially does the same as what C++ already does well at?), and many decisions were made based on lessons learned from complex C++ projects. As a result of the collective design decisions, Java and C# are more different from C++, than similar, from a systems perspective.

For example, for Java in 1995, James Gosling wrote these as design principles (today the document is at http://www.oracle.com/technetwork/java/intro-141325.html):

- simple, object-oriented, and familiar

- robust and secure

- architecture-neutral and portable

- high performance

- interpreted, threaded, and dynamic

Simplicity is a major thought, and is the weighing factor in trade-off decisions such as multiple inheritance. In particular, James Gosling also wrote in 1995 (https://cs.dartmouth.edu/~mckeeman/cs118/references/OriginalJavaWhitepaper.pdf) when elaborating the “simple” design principle:

JAVA omits many rarely used, poorly understood, confusing features of C++ that in our experience bring more grief than benefit. This primarily consists of operator overloading (although it does have method overloading), multiple inheritance, and extensive automatic coercions.

And obviously there are many technical reasons, such as what Chris Brumme said in 2003 about .NET (C#):

Multiple implementation inheritance injects a lot of complexity into the implementation. This complexity impacts casting, layout, dispatch, field access, serialization, identity comparisons, verifiability, reflection, generics, and probably lots of other places.

To me, this points out use cases for C# and Java that are more prevalent in the ‘newer’ class of applications, than when C and C++ were first developed. For example, today C++ is still well-suited for systems programming (e.g., writing Linux kernels, or systems software), whereas Java and C# tend to be used more for applications development. Seeing that these languages still dominate most language popularity indexes today, I think the design principles and decisions were directionally correct.

Complex Simplicity

Why does multiple inheritance get a bad rep? Why is it deemed to be adding more complexity than benefits? Typically, the ‘diamond problem’ is referenced (it even has more dramatic names such as “the dreaded diamond of death”).

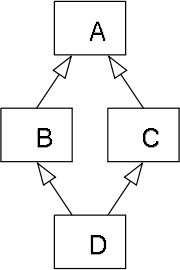

(from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Multiple_inheritance)

For example, we have classes B and C defined as subclasses of class A, and then class D (multiple) inherits from both B and C. Now in C++ this can be avoided, but in Java and C# every class is a subclass of Object, so by default this situation would surface with multiple inheritance. This adds complexity, because the compiler needs to handle these object relationships correctly, when allocating copies of each class A, B, C in the new D instance.

In C++:

class A { ... };

class B : public A { ... };

class C : public A { ... };

class D : public B, public C { ... };In this case, the compiler allocates a D object containing B and C, with B and C each containing its own instance of A, and so we’d end up with two independent A objects. Complications arise when we need to update a parent field, let’s say A::field, which either means needing to update it twice (through B::field and C::field), or allowing the chance for errors (e.g., new a pointer in B::field, and delete C::field). This is related to multiple inheritance of state, and how compilers need to allocate instance data from superclasses on the heap of the concrete subclass.

So C++ introduced virtual inheritance to address this issue (whereas the above would be considered multiple non-virtual inheritance):

class A { ... };

class B : public virtual A { ... };

class C : public virtual A { ... };

class D : public B, public C { ... };In this case, only one instance of A would be included in the derived class, and referenced using pointers instead; essentially creating the ‘diamond’ relationship for the D instance. But now we have complications in how object initializations are executed. The compiler initializes A in the D constructor, and pointers to it in B and C, then the rest members of the classes B, C, and D are initialized. However there’s an implicit rule that once the D constructor has initialized A, the B and C constructors are not allowed to re-initialize A again (because the compiler doesn’t know which constructor between B and C the programmer intended to use). This often causes runtime issues. Then there are additional complexities with assignment operators, type conversion, etc. that are more frequently used throughout a program, but would require extra attention to avoid pitfalls.

And then there’s multiple inheritance of implementation, where complexities arise when the compiler needs to figure out which method implementation should be called, when derived classes have overridden methods in base/super classes. Or, a programmer can unwittingly introduce a name conflict by adding a new method to a superclass (such as when we have D::method and B::method, then someone adds A::method - which implementation should be used when D::method is invoked?).

Of course, we can avoid these complexities by ‘not writing bad code’ and adding some work-arounds, such as not defining instance variables in super classes and to not use virtual inheritance, be more careful when defining methods (or extend instead of override in subclasses - but that’s kind of like taking a step towards object composition too), and maintain the code having a keen awareness of the intricacies and added complexities. It can work, and it has worked well in many cases.

However, this boils down to the observation that multiple inheritance isn’t a highly used construct/feature, and that more often than not, it is mis-used in practice, which results in creating the problems and complexities, and needing additional work-arounds just to use the feature. Multiple inheritance requires expert knowledge to do it well, otherwise it is relatively easy to run into pitfalls and create issues. In the end, because of the high potential for mis-use, it is deemed that the costs outweigh the benefits.

Fundamental Differences

And as we discussed, in most cases where multiple inheritance is considered, we can instead use techniques such as object composition, delegation, AOP with mixins, etc.; as opposed to thinking multiple inheritance as the only solution to accomplish implementation and/or state reuse. However, this is indeed considered a work-around to a useful feature. I have to write and maintain more code to make composition/delegation work, and more code when referenced classes/instances are updated (such as new methods I’d need to also add to the wrapper code), compared to effectively using multiple inheritance.

From this perspective, what Bjarne Stroustrup said in 2003 was particularly enlightening:

People quite correctly say that you don’t need multiple inheritance, because anything you can do with multiple inheritance you can also do with single inheritance. You just use the delegation trick I mentioned. Furthermore, you don’t need any inheritance at all, because anything you do with single inheritance you can also do without inheritance by forwarding through a class. Actually, you don’t need any classes either, because you can do it all with pointers and data structures. But why would you want to do that? When is it convenient to use the language facilities? When would you prefer a workaround? I’ve seen cases where multiple inheritance is useful, and I’ve even seen cases where quite complicated multiple inheritance is useful. Generally, I prefer to use the facilities offered by the language to doing workarounds.

To me this also pointed out some fundamental differences between C++ and Java/C#. C++ can be thought of as a large bag of tools (many language facilities/features), where in the hands of expert programmers it can be extremely versatile, and create well-engineered software. There are a lot of useful tools, but we have to know how to use them properly. Java and C# on the other hand, require a lower learning curve and can support a wide range of modern applications, precisely because their (comparatively more restrictive) language designs and implementations hide a lot of the complexities (hence not as easy to make mistakes).

The introduction of Java and C# also marked the transition between the age of expert systems programmers to the age of democratized applications programming for the masses. Where C/C++ places more weight towards flexibility, Java/C# derives power from restrictions/limits. So in a way, C/C++ and Java/C# are fundamentally different languages well-suited for somewhat different software development scenarios. Thus we don’t necessarily need to think, that because these are all ‘programming languages’ (that look especially similar), if one language has some useful features, then another language should have those same features too.

Personally, I kind of like it that differences in these languages exist, which help me focus on different things when developing different kinds of software. On the other hand, do I sometimes wish for some C++ features when working in Java/C#, or wish for the rich high-level frameworks in Java/C# from a C++ perspective? Sure I do; but not for long. It’s more fun to make things work so I just move on. 😉