Internet Service Bus and Windows Azure AppFabric

Microsoft’s AppFabric, part of a set of ”application infrastructure” (or middleware) technologies, is (IMO) one of the most interesting areas on the Microsoft platform today, and where a lot of innovations are occurring. There are a few technologies that don’t really have equivalents elsewhere, at the moment, such as the Windows Azure AppFabric Service Bus. However, its uniqueness is also often a source of confusion for people to understand what it is and how it can be used.

Internet Service Bus

Oh no, yet another jargon in computing! And just what do we mean by “Internet Service Bus” (ISB)? Is it hosted Enterprise Service Bus (ESB) in the cloud, B2B SaaS, or Integration-as-a-Service? And haven’t we seen aspects of this before in the forms of integration service providers, EDI value-added networks (VANs), and even electronic bulletin board systems (BBS’s)?

At first look, the term “Internet Service Bus” almost immediately draws an equal sign to ‘Enterprise Service Bus’ (ESB), and aspects of other current solutions, such as ones mentioned above, targeted at addressing issues in systems and application integration for enterprises. Indeed, Internet Service Bus does draw relevant patterns and models applied in distributed communication, service-oriented integration, and traditional systems integration, etc. in its approaches to solving these issues on the Internet. But that is also where the similarities end. We think Internet Service Bus is something technically different, because the Internet presents a unique problem domain that has distinctive issues and concerns that most internally focused enterprise SOA solutions do not. An ISB architecture should account for some very key tenets, such as:

- Heterogeneity – This refers to the set of technologies implemented at all levels, such as networking, infrastructure, security, application, data, functional and logical context. The internet is infinitely more diverse than any one organization’s own architecture. And not just current technologies based on different platforms, there is also the factor of versioning as varying implementations over time can remain in the collective environment longer than typical lifecycles in one organization.

- Ambiguity – the loosely-coupled, cross-organizational, geo-political, and unpredictable nature of the Internet means we have very little control over things beyond our own organization’s boundaries. This is in stark contrast to enterprise environments which provide higher-levels of control.

- Scale – the Internet’s scale is unmatched. And this doesn’t just mean data size and processing capacity. No, scale is also a factor in reachability, context, semantics, roles, and models.

- Diverse usage models – the Internet is used by everyone, most fundamentally by consumers and businesses, by humans and machines, and by opportunistic and systematic developments. These usage models have enormously different requirements, both functional and non-functional, and they influence how Internet technologies are developed.

For example, it is easy to think that integrating systems and services on the Internet is a simple matter of applying service-oriented design principles and connecting Web services consumers and providers. While that may be the case for most publicly accessible services, things get complicated very quickly once we start layering on different network topologies (such as through firewalls, NAT, DHCP and so on), security and access control (such as across separate identity domains), and service messaging and interaction patterns (such as multi-cast, peer-to-peer, RPC, tunneling). These are issues that are much more apparent on the Internet than within enterprise and internal SOA environments.

On the other hand, enterprise and internal SOA environments don’t need to be as concerned with these issues because they can benefit from a more tightly controlled and managed infrastructure environment. Plus integration in the enterprise and internal SOA environments tend to be at a higher-level, and deal more with semantics, contexts, and logical representation of information and services, etc., organized around business entities and processes. This doesn’t mean that these higher-level issues don’t exist on the Internet; they’re just comparatively more “vertical” in nature.

In addition, there’s the factor of scale, in terms of the increasing adoption of service compositions that cross on-premise and public cloud boundaries (such as when participating in a cloud ecosystem). Indeed, today we can already facilitate external communication to/from our enterprise and internal SOA environments, but to do so requires configuring static openings on external firewalls, deploying applications and data appropriate for the perimeter, applying proper change management processes, delegate to middleware solutions such as B2B gateways, etc. As we move towards a more inter-connected model when extending an internal SOA beyond enterprise boundaries, these changes will become progressively more difficult to manage collectively.

An analogy can be drawn from our mobile phones using cellular networks, and how its proliferation changed the way we communicate with each other today. Most of us take for granted that a myriad of complex technologies (e.g., cell sites, switches, networks, radio frequencies and channels, movement and handover, etc.) is used to facilitate our voice conversations, SMS, MMS, and packet-switching to Internet, etc. We can effortlessly connect to any person, regardless of that person’s location, type of phone, cellular service and network, etc. The problem domain and considerations and solution approaches for cellular services, are very different from even the current unified communications solutions for enterprises. The point is, as we move forward with cloud computing, organizations will inevitably need to integrate assets and services deployed in multiple locations (on-premises, multiple public clouds, hybrid clouds, etc.). To do so, it will be much more effective to leverage SOA techniques at a higher-level and building on a seamless communication/connectivity “fabric”, than the current class of transport (HTTPS) or network-based (VPN) integration solutions.

Thus, the problem domain for Internet Service Bus is more “horizontal” in nature, as the need is vastly broader in scope than current enterprise architecture solution approaches. And from this perspective Internet Service Bus fundamentally represents a cloud fabric that facilitates communication between software components using the Internet, and provides an abstraction from complexities in networking, platform, implementation, and security.

Opportunistic and Systematic Development

It is also worthwhile to discuss opportunistic and systematic development (as examined in The Internet Service Bus by Don Ferguson, Dennis Pilarinos, and John Shewchuk in the October 2007 edition of The Architecture Journal), and how they influence technology directions and Internet Service Bus.

Systematic development, in a nutshell, is the world we work in as professional developers and architects. The focus and efforts are centered on structured and methodical development processes, to build requirements-driven, well-designed, and high-quality systems. Opportunistic development, on the other hand, represents casual or ad-hoc projects, and end-user programming, etc.

This is interesting because the majority of development efforts in our work environments, such as in enterprises and internal SOA environments, are aligned towards systematic development. But the Internet advocates both systematic and opportunistic developments, and increasingly more so as influenced by Web 2.0 trends. Like “The Internet Service Bus” article suggests, today a lot of what we do manually across multiple sites and services, can be considered a form of opportunistic application; if we were to implement it into a workflow or cloud-based service.

And that is the basis for service compositions. But to enable that type of opportunistic services composition (which can eventually be compositing layers of compositions), technologies and tools have to be evolved into a considerably simpler and abstracted form such as model-driven programming. But most importantly, composite application development should not have to deal with complexities in connectivity and security.

And thus this is one of the reasons why Internet Service Bus is targeted at a more horizontal, and infrastructure-level set of concerns. It is a necessary step in building towards a true service-oriented environment, and cultivating an ecosystem of composite services and applications that can simplify opportunistic development efforts.

ESB and ISB

So far we discussed the fundamental difference between Internet Service Bus (ISB) and current enterprise integration technologies. But perhaps it’s worthwhile to discuss in more detail, how exactly it is different from Enterprise Service Bus (ESB). Typically, an ESB should provide these functions (core plus extended/supplemental):

- Dynamic routing

- Dynamic transformation

- Message validation

- Message-oriented middleware

- Protocol and security mediation

- Service orchestration

- Rules engine

- Service level agreement (SLA) support

- Lifecycle management

- Policy-driven security

- Registry

- Repository

- Application adapters

- Fault management

- Monitoring

In other words, an ESB helps with bridging differences in syntactic and contextual semantics, technical implementations and platforms, and providing many centralized management capabilities for enterprise SOA environments. However, as we mentioned earlier, an ISB targets concerns at a lower, communications infrastructure level. Consequently, it should provide a different set of capabilities:

- Connectivity fabric – helps set up raw links across boundaries and network topologies, such as NAT and firewall traversal, mobile and intermittently connected receivers, etc.

- Messaging infrastructure – provides comprehensive support for application messaging patterns across connections, such as bi-directional/peer-to-peer communication, message buffers, etc.

- Naming and discovery – a service registry that provides stable URI’s with a structured naming system, and supports publishing and discovering service end point references

- Security and access control – provides a centralized management facility for claims-based access control and identity federation, and mapping to fine-grained permissions system for services

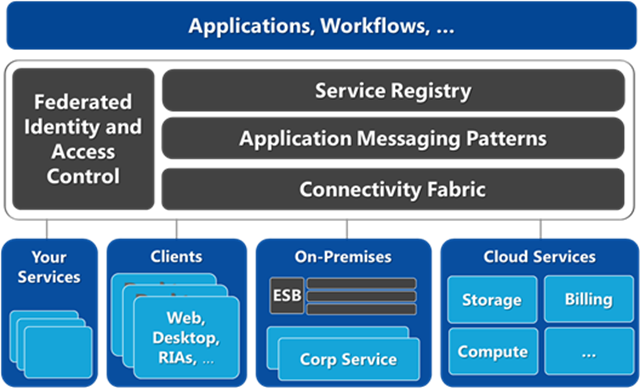

A figure of an Internet Service Bus architecture is shown below.

And this is not just simply a subset of ESB capabilities; ISB has a couple of fundamental differences:

- Works through any network topology; whereas ESB communications require well-defined network topologies (works on top)

- Contextual transparency; whereas ESB has more to do with enforcing context

- Services federation model (community-centric); whereas ESB aligns more towards a services centralization model (hub-centric)

So what about some of the missing capabilities that are a part of ESB, such as transformation, message validation, protocol mediation, complex orchestration, and rules engine, etc.? For ISB, these capabilities should not be built into the ISB itself. Rather, leverage the seamless connectivity fabric to add your own implementation, or use one that is already published (can either be cloud-based services deployed in Windows Azure platform, or on-premises from your own internal SOA environment). The point is, in the ISB’s services federation model, application-level capabilities can simply be additional services projected/published onto the ISB, then leveraged via service-oriented compositions. Thus ISB just provides the infrastructure layer; the application-level capabilities are part of the services ecosystem driven by the collective community. On the other hand, for true ESB-level capabilities, ESB SaaS or Integration-as-a-Service providers may be more viable options, while ISB may still be used for the underlying connectivity layer for seamless communication over the Internet. Thus ISB and ESB are actually pretty complementary technologies. ISB provides the seamless Internet-scoped communication foundation that supports cross-organizational and federated cloud (private, public, community, federated ESB, etc.) models, while ESB solutions in various forms provide the higher-level information and process management capabilities.

Windows Azure AppFabric Service Bus

The Service Bus provides secure messaging and connectivity capabilities that enable building distributed and disconnected applications in the cloud, as well hybrid application across both on-premise and the cloud. It enables using various communication and messaging protocols and patterns, and saves the need for the developer to worry about delivery assurance, reliable messaging and scale.

In a nutshell, the Windows Azure AppFabric Service Bus is intended as an Internet Service Bus (ISB) solution, while BizTalk continues to serve as the ESB solution, though the cloud-based version of BizTalk may be implemented in a different form. And Windows Azure AppFabric Service Bus will play an important role in enabling application-level (as opposed to network-level) integration scenarios, to support building hybrid cloud implementations and federated applications participating in a cloud ecosystem.

(originally published at https://blogs.msdn.microsoft.com/dachou/2011/03/24/internet-service-bus-and-windows-azure-appfabric/)