Strong User Authentication on the Web

Focusing on methods that are used to implement strong user authentication for online-consumer identities, this article aims to distill a comprehensive view of strong user authentication by examining its concepts, implementation approaches, and challenges/additional concerns at the architectural level. It discusses effective solution approaches, overall architecture design, and emerging developments. (10 printed pages)

Introduction

Identity theft remains one of the more prevalent issues on the Internet today. Studies indicate that digital identity fraud is still on the rise, with an increase in sophistication (that is, “phishing,” “man-in-the-middle,” DNS poisoning, malware, social engineering, and so forth) and an expansion of attack vectors (that is, unregulated financial systems, lottery and sweepstakes contests, healthcare data, synthetic identities, and so on). With the upward trend of moving data and services into the Web and cloud-based platforms, the management and control of access to confidential and sensitive data is becoming more than verifying simple user credentials at the onset of user sessions for one application, and with higher interconnectivity and interdependencies among multiple applications, services, and organizations.

One of the more exploited methods today is the gaining of account access by stealing reusable credentials for Web sites that have not yet implemented “strong” user authentication. This is so, because most common forms of credentials today are knowledge-based (that is, user ID and password) and are requested only once during sign-on, which provides a higher level of convenience to users, but also requires less effort for attackers to exploit. Many attacks are manifested as “phishing” messages that masquerade as ones that are sent by legitimate organizations and contain URLs that point to fraudulent Web sites that have the same appearances as genuine ones. Often, they act as “man-in-the-middle” and eventually do forward visitors to the actual Web sites; but, in the process, they have captured valid credentials that can be used to gain access to actual accounts.

The ease with which online identities can be stolen and used effectively has prompted many organizations and governing bodies to raise alarms. In the U.S., the October 2005 Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council (FFIEC) “Authentication in an Internet Banking Environment” guide identified that simple-password authentication is insufficient for ensuring authorized access to important financial services. Many other regulatory provisions also have identified similar needs, such as the Homeland Security Presidential Directive (HSPD)-12, Electronic Signatures in Global and National Commerce (E-SIGN) Act, Federal Information Processing Standards Publication (FIPS PUB) 201-1, HIPAA, SOX, GLBA, PATRIOT, and so on.

Subsequently, various methods have been developed to improve the “strength” of an authentication system in withstanding identity-theft attacks. While the spectrum of methods spans a wide range of concern areas—such as enterprises, consumers, hardware, mobility, and so on—this article focuses on methods that are used to implement strong user authentication for online-consumer identities. It discusses effective solution approaches, overall architecture design, and emerging developments.

Strong User Authentication

So, how do we improve Web-based user-authentication systems without compromising usability and ubiquity, when the Internet is accessed mostly through a browser that has limited access to the client environment and hardware devices? The most common solution approaches that are used today involve, in more generalized terms, various forms of enhanced shared-secret and/or multifactor authentication.

Enhanced shared-secret authentication refers to extensions of conventional knowledge-based (single-factor) authentication—for example, additional passwords, site keys, preregistered graphical icons to support mutual authentication, challenge-response, randomized code selections that are based on input patterns, CAPTCHA, and so on.

Multifactor authentication refers to a compound implementation of two or more classes of human-authentication factors:

- Something known to only the user—Knowledge-based (for example, password, pass phrase, shared secrets, account details and transaction history, PIN, CAPTCHA, and so on).

- Something held by only the user—Possession-based (for example, security token, smart card, shared soft tokens, mobile device, and so on).

- Something inherent to only the user—Biological or behavior biometric traits (for example, facial recognition, fingerprint, voice recognition, keystroke dynamics, signature, and so on).

For example, many enterprise extranet/VPN solutions today require both simple credentials (something known, such as ID and password) and hardware tokens (something held, such as secure ID with time-based one-time password generators, smart cards that use embedded PKI solutions, and so on) in order to gain access. The combination of the two “known” and “held” factors makes up the multifactor authentication method, and significantly improves the authentication strength, as it curtails the threat of stolen digital identities.

In practice, however, there is a wealth of implementations, methods, and permutations of them—all with varying trade-offs in terms of cost, complexity, usability, and security. Next, let’s discuss viable solution approaches.

Solution Approaches

Now, not all of the available strong-authentication options that are available today lend themselves well to the Web. Conventional multifactor authentication methods (that involve the deployment of custom hardware tokens, such as RSA SecurID, smart cards, and so on) are effective for closed communities—such as employees and partners—but they are too costly, inconvenient, and logistically difficult—for example, distribution, administration, management, support, and so on—for the open consumer communities on the Web. In this case, authentication solutions have to work primarily within the confines of the browser’s security sandbox. Here, we discuss a few solution approaches that are relatively cost-effective to implement for online consumers, based on today’s standards:

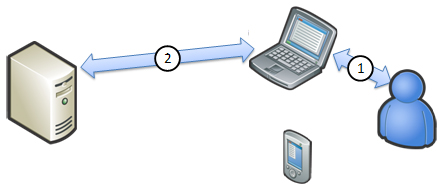

Figure 1a. Knowledge-based authentication

Knowledge-based authentication (KBA) typically is implemented as extensions to existing simple-password authentication. Knowledge-based credentials include chosen information, personal and historical information, on-hand information, deductive and derived responses, patterns, images, and so on. However, it generally boils down to additional set(s) of challenge-response that allows users to prove that the claimed identities belong to them. Some well-known examples include Bank of America’s “SiteKey,” HSBC’s virtual keyboard, and so on. KBA is used also as an identity-verification method for self-service password-reset processes; but, when implemented effectively, they can be used as methods to complement primary authentication. This approach moderately improves authentication strength, as it is still single-factor (in-band within the browser) and prone to phishing attacks, but it might be sufficient for some Web sites.

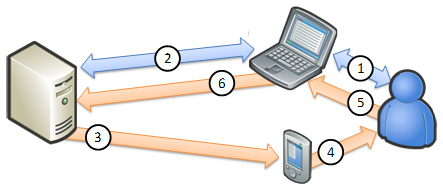

Figure 1b. Server-generated OTP

Server-generated one-time passwords (OTPs) commonly are implemented as randomized password strings that are generated in real time after verifying simple-password credentials. Some more advanced implementations combine KBA elements to facilitate derived OTPs (such as server-generated grid cards for shared pattern recognition, digitally signed OTPs that are based on server-generated data, and so on). The generated OTPs then are delivered to users via a different channel (out-of-band) from the session in the browser, such as e-mail, SMS (Short Message Service) text messaging to mobile devices, direct phone calls that use computer-generated speech, and so on. Users then can use the OTP to sign-in to the application, by entering it into a designated field on the page.

Many organizations in the public sector have started to deploy this type of solution to implement strong user authentication. This approach significantly improves authentication strength as it employs two-factor authentication and out-of-band delivery of OTPs. However, it still is not completely secure, as it is prone to the “man-in-the-middle” real-time phishing attacks that try to capture and use the OTP in real time. Plus OTP delivery latencies potentially could affect overall user experience.

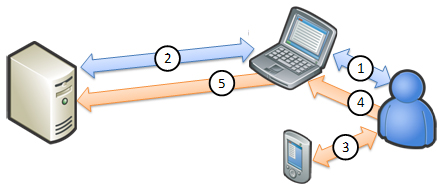

Figure 1c. Client-generated OTP

Client-generated one-time passwords are similar to conventional OTP hardware tokens (such as RSA SecurID, VeriSign VIP OTP, and so on). However, with the level of near-ubiquitous proliferation of mobile devices today, cellular phones have become a viable alternative as the soft-token (or “something held”) authentication factor. In this case, individualized cryptographic software components can be installed on mobile devices to generate time-based or event-based OTPs. Users then can use the OTP to sign-in to the application after authenticating simple Web-based credentials (examples include RSA SecurID software, Java ME applications, and so on). This approach has the benefits of OTPs, not having to deal with out-of-band delivery latencies and inconsistent service coverage.

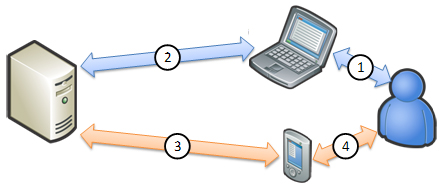

Figure 1d. Out-of-band authentication

Out-of-band (OOB) authentication leverages the second factor for authentication, instead of delivery of individualized information. Current implementations include speech recognition that is facilitated via out-bound or in-bound voice calls (to/from land or cellular lines) or KBA via SMS request/reply. This type of solution offers higher authentication strength, as both the browser and a second factor are used to verify credentials, which works to impede common phishing attacks.

In general, these high-level approaches rank in increasing relative authentication strength. However, higher authentication strength does not necessarily represent the best-of-breed solution, as security often requires trade-offs in user convenience. Studies indicate that different user populations respond differently to strong-authentication methods. The choice of an approach (or combinations of approaches) should consider user segments, as well as the types of activities and interactions that they perform with the application. For example, online consumers who view account balances (considered a relatively low-risk type of activity) should require comparatively less effort to access than consumers who conduct account transfers or physicians who view patient’s medical records.

Finally, the implementation of strong user authentication often is a balancing act between security and usability. Many implementations have not achieved their intended effectiveness by either delivering significantly deteriorated user experiences or compromising security postures by simply satisfying requirements on paper. Furthermore, there is no one-size-fits-all solution approach. For example, not all Web sites require multifactor authentication, while enhanced knowledge-based authentication might be “secure enough”; and some carefully designed single-factor methods actually might be “stronger” than some multifactor methods. A well-balanced design tends to be more cost-effective than force-fitting various best-of-breed approaches into one solution.

Architectural Perspectives

We’ve just discussed how strong user authentication can be implemented as a component of a Web application architecture. Are there other areas of concerns and challenges that we should pay attention to, and how does this component affect or relate to the rest of the architecture?

From an architectural perspective, strong user authentication involves more than just ensuring an effective identity and credentials verification at the point of user sign-on. A fully integrated and highly coordinated architecture is required to deliver an effective strong user authentication. Let’s discuss here the more prevalent aspects and challenges of a strong user-authentication architecture.

Identity Proofing

Identity proofing is the process of verifying user identities (for example, if a user is indeed who the individual claims to be) before provisioning user credentials. A strong user-authentication implementation is ineffective, and the identity infrastructure becomes unreliable, if verifiable identity assurance cannot be ensured.

In-person identity proofing that is based on valid IDs and credentials remains one of the more reliable methods today, and is commonly used by various financial, government, and healthcare organizations. On the other hand, in self-service scenarios in which identity proofing is handled completely online, organizations typically use knowledge-based systems to verify user identities. However, in this case, the pieces of information that are requested from an individual for identification purposes should be resistant to social-engineering attacks.

Furthermore, the same level of identity proofing is required also when reissuing credentials (for example, resetting passwords, recovering forgotten IDs, requesting elevated access, and so on) and terminating credentials. Compromising the level of strength in identity proofing in any stage of an identity’s life cycle will affect adversely the overall effective authentication strength.

The point at which user provision occurs is also where additional authentication factors should be registered and associated with a new user’s profile; these factors are used then to support strong user authentication—for example, answering sets of challenge-response to support KBA, registering/verifying a mobile phone number to support out-of-band OTP delivery, capturing voice recordings to support speech recognition, and so forth.

Integration Architecture

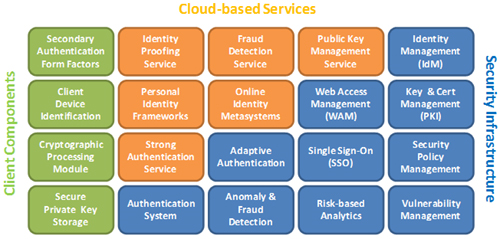

A comprehensive, robust, and reliable user-authentication system is becoming more than a database-driven component of one stand-alone application. A strong-authentication system must be tightly integrated and synchronized with the security infrastructure in an organization, such as identity management (IdM), Web access management (WAM), enterprise single sign-on (ESSO), certificate and key management (PKI), vulnerability management, audit management, policy management, user directories/repositories, and so on. In some cases, these systems provide capabilities that can be leveraged to implement a strong-authentication system, while some downstream systems depend on the authentication system to pass relevant contextual information and authenticating decisions (for example, role-mapping) that are needed for user authorization and access control.

Increasingly, an organization’s security infrastructure will include capabilities that live in the cloud (or are hosted by other service providers). Although these services do not reside in an organization’s own infrastructure, the same integration concerns and security-access policies and requirements still must be applied consistently, in order to maintain a uniformly reliable security architecture.

Layered Approach

The initial logon page does not have to be the only point at which users are authenticated. A layered approach can be implemented, so that different strength levels of authentication are implemented in different areas, according to the varying levels of data confidentiality and/or value. When it is implemented with a balanced design between data requirements and authentication strengths and points, this approach can improve overall usability while ensuring security, as it allows convenient access to less confidential areas of a Web site, and more credentials are required only to access the more confidential areas. Furthermore, additional authentication/verification can be required on individual transactions that are deemed more risky. These potentially can leverage the stronger authentication methods, such as multifactor and out-of-band authentication approaches.

Alternatively, in systems that have implemented role-based access control (RBAC) for user authorization, different methods of authentication can be presented to users who are mapped to different roles; or, in a more dynamic implementation, if a user logs on by using partial credentials (when higher-strength credentials are made optional), that user is mapped to a role that has lower access privileges for that Web session.

Risk-Based Analytics

Risk-based analytics are similar to what credit card companies use to assess risk levels for each requested transaction and make authorization decisions in real time. Assessments are based on real-time evaluation of various data points that are collected about the user and the requested transaction; depending on the scoring and data-confidentiality requirements, a transaction can be authorized or unauthorized, or additional credentials can be requested from the user to facilitate stronger authentication and reliable auditing.

The data points that are collected often are contextual information (or location-based, behavior-based, and so on) and used as supplemental credentials to support strong authentication. For example, client-device identification (CDI) can be used to simplify valid repeated authentication requirements from the same client device, if a verified set of credentials has signed in to a Web site from the same device previously. This is often facilitated by saving specific “remember me” cookies, and sometimes by using a combination of data points that are collected from the HTTP request and client-side JavaScript code. Subsequently, based on the risk-based assessment that the same user had signed in successfully to the same application previously, a lower-strength authentication is presented to the user to improve convenience.

Historical and social data points also are included often in the risk assessment, and often are used from the perspective of transaction-anomaly detection (TAD), as these data points help establish a “normal” usage profile about a user and can be compared against the requested transaction to identify contextual anomalies. For example, a transaction that is identified with unusual characteristics (for example, originating from a different physical location, different client device, unusual time of day/week, fund transfers to new and unverified account, and so on) contributes to a higher risk profile, which prompts the authentication system to require stronger authentication from the user in order to authorize the transaction.

This is also referred to as fraud detection, and it works well together with a layered approach to implement a dynamically adaptive authentication system.

Compensating Controls

An authentication system also can take into account other components that are not integrated directly into this architecture, which can potentially influence (positively or negatively) users’ security postures and/or risk profiles, and contribute to risk-based analysis. For example, Extended Validation SSL (EV-SSL), digital watermarking, site keys, and so on contribute to mutual authentication and help improve end-user behavior, which in a way improves the risk profile. Host intrusion detection, anti-spyware, anti-phishing network services, and so on all contribute to a user’s overall risk profile.

Figure 2: Strong user authentication architecture components

Finally, the view of authentication architecture that is presented here falls on the more comprehensive and complex side of the various design approaches. It certainly is not required for all organizations to implement all of the identified capabilities, but can serve as a reference to each implementation project to support evaluation of required capabilities, and assess how they should be implemented—although some complex enterprise environments might require this level of meticulous planning and design in order to deliver an effective identity-assurance infrastructure and proficiently safeguard important data.

However, regardless of how simple or complex each implementation might be, it is necessary that security policies and authentication systems be applied homogeneously to all user-contact surfaces. An inconsistent implementation across the entire operational architecture could expose certain loopholes for attackers to exploit; and, sometimes, these can include nontechnical areas, such as administrative processes, instructions for call-center customer service reps, and so on.

State-of-the-Art

Several emerging megatrends also influence developments in the online user-authentication space. Let’s discuss both their impacts and how they are related to strong user-authentication concerns.

Cloud Computing

From a user-authentication perspective, moving data into the cloud and integrating cloud-based services should be implemented with the same level of overall effective authentication strength as the enterprise perspective of authentication architecture. However, organizations have significantly less control over the authentication strengths of the interdependent cloud-based services of their counterparts/partners. For example, whether via identity federation or delegation, the overall security posture of the resulting interconnected architecture can be compromised if the integrated services themselves have comparatively lower-strength authentication systems in place.

The same is true for SaaS (software-as-a-service) providers, as extra attention must be focused on ensuring appropriate levels of authentications strengths for different user communities in a multitenancy model, without compromising overall and individual security and usability.

Thus, the focus on authentication systems becomes one of the primary evaluation factors for organizations that are looking to adopt cloud-based services. Organizations must ensure that service providers provide the flexibility to deliver varying levels of strong authentication to meet required security policies, or extend existing security implementations by leveraging identity federation (via SAML or WS-Federation) or authentication delegation to support single sign-on (SSO) or reduced sign-on (RSO). However, in these cases, organizations must incur the costs to deploy secure and accessible identity-federation and/or authentication-delegation services.

From a capabilities perspective, many of the authentication architecture components are being deployed as cloud-based services—for example, identity-proofing services that are deployed by credit bureaus, consumer-identity frameworks and providers, vulnerability-management networks, PKI and certificate-management services, secondary-factor channel providers (voice telephony, SMS messaging, speech recognition, patterns recognition, and so forth), fraud detection, strong-authentication service providers, and so on. These services provide much-needed capabilities to compose a strong-authentication system; however, the same integration-security concerns remain such that any one weak link in the connected-systems architecture will compromise the overall security posture.

Identity Metasystems

The consumer-identity frameworks that are available now as cloud-based platforms and their growing adoption means that organizations eventually will need to integrate these identity metasystems to improve user convenience—for example, OpenID identity providers, Google Account, Windows Live ID, Yahoo! ID, and so on—although, in order to integrate these online communities, the authentication strengths that are implemented for these services must be evaluated against the security policies and requirements for the organizations that are looking to leverage them.

Similarly, online identity providers increasingly will need to add flexibility to configure varying levels of authentication strengths for different user segments, in addition to integrating various authentication form factors and standards (Higgins, PKCS, OpenID, Windows Cardspace, and so on) if they intend to provision services to data-sensitive organizations.

Smart-Card Proliferation

With the availability of more sophisticated smart-card solutions and ecosystem support, more physical credentials are adopting smart-card (standard plastic cards embedded with microprocessors and/or integrated circuits) deployments. For example, many countries and states (for example, Austria, Belgium, Estonia, Hong Kong, and Spain) already have rolled out government-sponsored electronic ID programs to national citizens. Subsequently, smart cards are becoming another form of authentication factor, where smart-card readers are available and are integrated into authentication systems.

Furthermore, many vendors are consolidating multiple authenticators into the ISO 7816 smart-card form factor—for example, integrated LCDs to display OTPs, and biometric (fingerprint) readers. We might find smart-card deployments materialize in more cases, such as from financial institutions that already are issuing physical credentials (that is, credit cards, debit cards, and so on). Cryptographic smart cards that use biometric readers provide very high identity assurance, as they tightly bind the private keys to the users’ biometrics (multifactor authentication).

Mobile Identity

From a physical-hardware perspective, SIM (Subscriber Identity Module) cards have improved significantly in terms of storage capacity and capability to perform cryptographic processing. Computing power and memory capacity also have improved exponentially in mobile devices. Subsequently, the SIM card and mobile phone have become the smart card and smart-card reader that constitute the most ubiquitous “something held” (or in-possession) authentication factor.

This makes it possible to store symmetric keys on SIM cards and, along with simple cryptographic software modules, to turn the mobile device into a seeded OTP generator. The generated OTPs can be used as credentials for out-of-band, multifactor authentication.

Furthermore, with wireless data plans, mobile devices can communicate directly with authentication systems by using wireless PKI. In this case, SIM cards provide secure storage of users’ private PKI keys. The private keys then can be used to facilitate strong authentication—implemented with corresponding certificates to facilitate digital signatures—and, in some cases, to facilitate client-authenticated SSL. Some of the projected applications of this approach include mobile banking, contactless/proximity mobile payments, identity and credential verification, and so on. At some point, mobile devices might become the most ubiquitous form of mobile digital identities for consumers.

Final Thoughts

So, it appears that a user-authentication system for consumer communities on the Web is growing beyond the traditional database-driven and/or directory-driven component of a Web application, for organizations that have higher data-confidentiality requirements. Implementation approaches for strong authentication span a full spectrum that ranges from highly integrated and interconnected/dependent to simple extensions of existing stand-alone architectures.

Building a strong user-authentication architecture requires focus beyond just improving the credential-verification component. The overall architecture might include additional aspects, such as a layered system that is driven by risk-based analytics, which enables an adaptive authentication system. Also, the design of an authentication approach should be weighed against various requirements, such as data (that is, availability, confidentiality, integrity, accountability, and so on), identity assurance, usability, compliance and auditing, portability/scalability, manageability, and user-community dynamics. More importantly, however, just the same as other security initiatives, strong user authentication also requires a carefully planned, well-balanced, and concerted approach across the entire IT architecture to ensure a consistently secure environment.

With the growing adoption of cloud-based services, consumer-identity metasystems, and mobile devices, while attack methods gain maturity and sophistication, the future outlook for strong user authentication is set for many innovative developments.

Conclusion

The escalating trend of moving data and services into the cloud also necessitates methodical planning to ensure secure access to authorized users over the Internet. While existing simple-password–based authentication might continue to work for many consumer-oriented Web sites, its inherent vulnerabilities have been identified as security risks for institutions that have higher data-privacy requirements. To mitigate the risk of online identity fraud, organizations look to strong user authentication as the solution for improving their Web-based authentication systems.

However, implementing strong user authentication often is not a straightforward task, as projects have myriad options from which to choose, a multitude of trade-offs to consider, and a cluster of intricacies to manage. This article has intended to distill a comprehensive view of strong user authentication by examining its concepts, implementation approaches, and challenges and additional concerns at the architectural level.

Resources

- Authentication in an Internet Banking Environment, Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council. http://www.ffiec.gov/pdf/authentication_guidance.pdf

- Electronic Authentication Guideline v1.0.1, National Institute of Technology Special Publication 800-63 (NIST SP 800-63). http://csrc.nist.gov/publications/nistpubs/800-63/SP800-63V1_0_2.pdf

- Policy for a Common Identification Standard for Federal Employees and Contractors, Homeland Security Presidential Directive-12 (HSPD-12). http://www.whitehouse.gov/news/releases/2004/08/20040827-8.html

- Personal Identity Verification of Federal Employees and Contractors, Federal Information Processing Standards Publication 201-1 (FIBS PUB 201-1). http://csrc.nist.gov/publications/fips/fips201-1/FIPS-201-1-chng1.pdf

- Electronic Signatures in Global and National Commerce Act, United States Congress E-SIGN Act. http://frwebgate.access.gpo.gov/cgi-bin/getdoc.cgi?dbname=106_cong_bills&docid=f:s761enr.txt.pdf

- A Guide to Understanding Identification and Authentication in Trusted Systems, National Computer Security Center (NCSC-TG-017). http://www.csirt.org/color_%20books/NCSC-TG-017.pdf

- Computer Security Guidelines for Implementing the Privacy Act of 1974, FIPS PUB 41. http://www.itl.nist.gov/fipspubs/fips41.pdf

- Security Requirements for Cryptographic Modules, FIPS PUB 140-2. http://csrc.nist.gov/publications/fips/fips140-2/fips1402.pdf

About the author

David Chou is an architect in the Developer & Platform Evangelism organization at Microsoft, where he collaborates with local organizations in architecture, design, and proof-of-concept projects. Drawing on experiences from his previous jobs at Accenture and Sun Microsystems, David enjoys helping customers create value from using objective and pragmatic approaches to define IT strategies and solution architectures. David maintains a blog at http://blogs.msdn.microsoft.com/dachou, and can be reached at david.chou@microsoft.com.

This article was published in the Architecture Journal, a print and online publication produced by Microsoft. For more articles from this publication, please visit the Architecture Journal Web site.

(originally published at https://msdn.microsoft.com/en-us/cc838351.aspx)